[Norsk]

"States should impose an absolute ban on all forced and non-consensual medical interventions against persons with disabilities, including the non-consensual administration of psychosurgery, electroshock and mind-altering drugs, for both long- and short- term application. Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan E Méndez 4. mars 2013

Based on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (UN 2018a), several UN bodies, among them the High Commissioner for Human Rights, have argued for a complete ban of all coercive interventions in mental health care (UN 2013, 2014, 2017a, 2017b, 2018b). In 2014, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities called for states to “abolish policies and legislative provisions that allow or perpetrate forced treatment” (UN 2014), arguing that it is an “ongoing violation found in mental health laws across the globe, despite empirical evidence indicating its lack of effectiveness and the views of people using mental health systems who have experienced deep pain and trauma as a result of forced treatment.”

According to the Committee, forced treatment violates Article 12 of the Convention, equal recognition before the law, and several other articles such as the right to personal integrity (Art. 17), freedom from torture (Art. 15) and freedom from violence, exploitation, and abuse (Art. 16). The Committee perceives forced treatment to deny the legal capacity of a person to choose medical treatment, therefore classifying it as a violation of Article 12 of the Convention (UN 2014).

Similarly, the 2017 report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health argues for “measures to radically reduce medical coercion and facilitate the move towards an end to all forced psychiatric treatment and confinement.” (UN 2017b). Additionally, in 2017, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights held that “many practices within mental health institutions also contravene articles 15, 16 and 17 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Forced treatment and other harmful practices, such as solitary confinement, forced sterilization, the use of restraints, forced medication and overmedication (including medication administered under false pretenses and without disclosure of risks) not only violate the right to free and informed consent, but constitute ill-treatment and may amount to torture.” (UN 2017a). Consequently, this report supports the abolition of all involuntary treatment and the adoption of measures to ensure that health services including all mental health services are based on the free and informed consent of the person concerned, as stipulated by the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and “the elimination of the use of seclusion and restraints, both physical and pharmacological.” (UN 2017a).

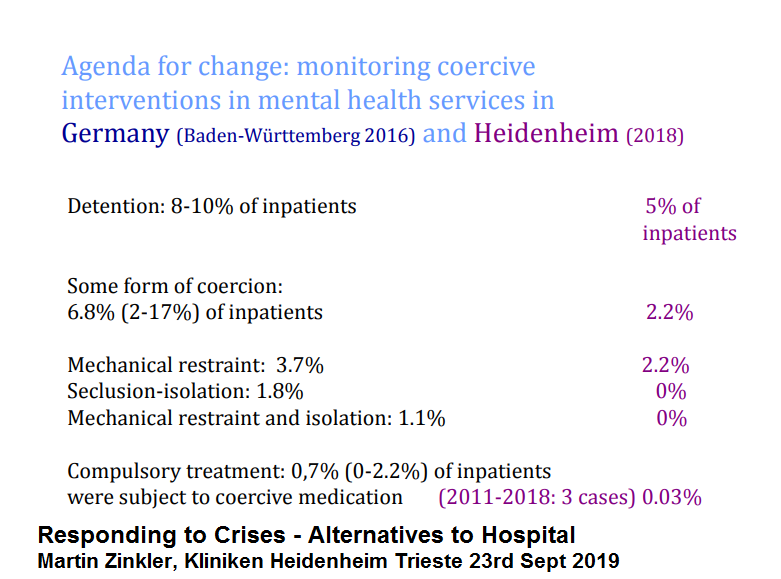

All these postulations, however, are in stark contrast with the reality of mental health care. Even though mental health care practices and mental health law vary around the globe, they also share a long history of coercion, detention, rights violation, and detainment. Even if most current mental health care systems offer support of various intensity and degree, they also use coercive interventions (e.g., mechanical restraint (being tied to a bed frame); chemical restraint (being injected with tranquilizers); isolation (being locked in a room); detention in hospital or being brought to a mental health facility by the police with the use of force). The frequency and intensity of coercive interventions in mental health care vary (Kallert et al. 2005) and systematic recording is only in place in some countries (for a register on coercive interventions in Germany see (Flammer and Steinert 2018)).

The response from psychiatry has mainly been critical, defending the need for coercion and going as far as accusing the Committee of “reversing hard won victories in the name of human rights” (Freeman et al. 2015) or suggesting that governments “ignore the Convention when it would interfere with a commonsense approach to protecting citizens who in one way or another are incapable of protecting themselves.” (Applebaum 2019)

The authors Martin Zinkler and Sebastian von Peter conceptualize a system for mental health care based on support only. Psychiatry loses its function as an agent of social control and follows the will and preferences of those who require support. The authors draw up scenarios for dealing with risk, inpatient care, police custody, and mental illness in prison. With such a shift, mental health services could earn the trust of service users and thereby improve treatment outcomes (1).

Germany without Coercive Treatment in Psychiatry—A 15 Month Real World Experience 2011 to 2012 showed that it is possible to reduce forced drugging by 90% (2) down to 0.6% on forced medication. Additional training of personnel could nearly remove forced drugging, i. e. only 0,03 % of patients where subject to coercive medication 2011 to 2018 in Heidenheim hospital in Germany. (3)

References:

Martin Zinkler et al. 2019: "End Coercion in Mental Health Services—Toward a System Based on Support Only", Laws 2019, 8(3), 19; https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8030019

Martin Zinkler: «Germany without Coercive Treatment in Psychiatry—A 15 Month Real World Experience», Laws 2016, 5(1), 15; https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5010015

Responding to Crises - Alternatives to Hospital: Martin Zinkler, Kliniken Landkreis Heidenheim gGmbH, Trieste 23rd Sept 2019: http://www.triestementalhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Zinkler.pdf